March 11 is the Feast of Saint Óengus of Tallaght or Óengus the Culdee

“Óengus mac Óengobann, better known as Saint Óengus of Tallaght or Óengus the Culdee, was an Irish bishop, reformer and writer, who flourished in the first quarter of the 9th century and is held to be the author of the Félire Óengusso (“The Martyrology of Óengus”) and possibly the Martyrology of Tallaght.

Little of Óengus’s life and career is reliably attested. The most important sources include internal evidence from the Félire, a later Middle Irish preface to that work, a biographic poem beginning Aíbind suide sund amne (“Delightful to sit here thus”) and the entry for his feast-day inserted into the Martyrology of Tallaght…

It is sufficiently clear that Óengus became a cleric, since he describes himself as such in the Félire using the more humble appellation of “pauper” (pauperán and deidblén in Old Irish). He was an important member of the community founded by St. Máel Ruain at Tallaght (now in South Dublin), in the borderlands of Leinster. Máel Ruain is described as his mentor (aite, also “fosterfather”). There are reasons for believing that Óengus was ordained to the office of bishop, a denomination which is first assigned to him in a list of saints inserted into the Martyrology of Tallaght. If so, his influence may well have extended to the reformed communities which were associated with Tallaght, many of which were founded in Óengus’s lifetime. In fact, two such monasteries in Co. Limerick and Co. Laois, both of them known as Dísert Óengusa (“Óengus’s Hermitage”), bear his memory in name..

According to the Martyrology of Tallaght, Óengus’s feast-day, and hence the date of his death, is 11 March. The poem beginning Aíbind suide sund amne claims that he died on a Friday in Dísert Bethech (“The Birchen Hermitage”). Together, these have produced a range of possible dates such as 819, 824 and 830, but pending the dates of the martyrologies, no conclusive answer can be offered. His metrical Life tells that he was buried in his birthplace Clonenagh..

Becoming a hermit, he lived for a time at Disert-beagh, where, on the banks of the Nore, he is said to have communed with the angels. From his love of prayer and solitude he was named the “Culdee”; in other words, the Ceile Dé, or “Servant of God.” Not satisfied with his hermitage, which was only a mile from Clonenagh, and, therefore, liable to be disturbed by students or wayfarers, Óengus removed to a more solitary abode eight miles distant. This sequestered place, two miles southeast of the present town of Maryborough, was called after him “the Desert of Óengus”, or “Dysert-Enos”. Here he erected a little oratory on a gentle eminence among the Dysert Hills, now represented by a ruined and deserted Protestant church.

His earliest biographer in the ninth century relates the wonderful austerities practised by St. Óengus in his “desert”, and though he sought to be far from the haunts of men, his fame attracted a stream of visitors. The result was that the good saint abandoned his oratory at Dysert-Enos, and, after some wanderings, came to the monastery of Tallaght, near Dublin, then governed by St. Maelruain. He entered as a lay brother, concealing his identity, but St. Maelruain soon discovered him and collaborated with him on the Martyrology of Tallaght.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aengus_the_Culdee

Aengus was born of the royal house of Ulster and was sent to the monastery of Clonenagh by his father Oengoba to study under the saintly abbot Maelaithgen. He made great advances in scholarship and sanctity but eventually felt he had to leave and become a hermit to escape the adulation of his peers. He chose a spot some seven miles away for his hermitage which is still called Dysert.

He lived a life of rigid discipline, genuflecting three hundred times a day and reciting the whole of the Psalter daily, part of it immersed in cold water, tied by the neck to a stake. At his dysert he found he got too many visitors and went to the famous monastery of Tallaght near Dublin, without revealing his identity, and was given the most menial of tasks. After seven years a boy sought refuge in the stable where Aengus was working because he was unable to learn his lessons. Aengus lulled him to sleep and when he awoke he had learnt his lesson perfectly.

When the abbot of St. Maelruain heard of this monk’s great teaching gifts he recognised in him the missing scholar from Clonenagh and the two became great friends. It was at Tallaght that Aengus began his great work on the calendar of the Irish saints known as the Felire Aengus Ceile De. As for himself he thought that he was the most contemptible of men and is said to have allowed his hair to grow long and his clothing to become unkempt so that he should be despised. Besides the Felire one of his prayers asking for forgiveness survives, pleading for mercy because of Christ’s work and His grace in the saints.

Like all the holy people of God, Aengus was industrious and had a supreme confidence in His power to heal and save. On one occasion when he was lopping trees in a wood he inadvertently cut off his left hand. The legend says that the sky filled with birds crying out at his injury, but St. Aengus calmly picked up the severed hand and replaced it. Instantly it adhered to his body and functioned normally.

When St. Maelruain died in 792, St. Aengus left Tallaght and returned to Clonenagh succeeding his old teacher Maelaithgen as abbot and being consecrated bishop. As he felt death approaching he retired again to his hermitage at Dysertbeagh, dying there about 824. There is but scant evidence of the religious foundations at Clonenagh or Dysert but he will always be remembered for his Feliere, the first martyrology of Ireland.

http://www.oodegr.com/english/biographies/arxaioi/Angus%20of%20Culdee.htm

“..during his servitude at Tallaght, and amidst such surroundings as these, the saint composed his famous metrical Festology of the Saints.

The poem is divided into three principal parts, with subdivisions, consisting altogether of 690 quatrains. The Invocation is written in what modem Gaelic scholars call English chain verse; that is, an arrangement of metre by which the first words of every succeeding quatrain are identical with the last words of the preceding one. The following literal translation gives the dry bones, as it were, of the Invocation, while leaving out all the colour and harmony of the verses which ask grace and sanctification from Christ on the poet’s work:

Sanctify, O Christ ! my words:

O Lord of the seven heavens !

Grant me the gift of wisdom,

O Sovereign of the bright sun !

O bright son who dost illuminate

The heavens with all their holiness !

O King who governest the angels !

O Lord of all the people !

Lord of the people,

King all-righteous and good !

May I receive the full benefit

Of praising Thy royal hosts.

Thy royal hosts I praise

Because Thou art my Sovereign ;

I have disposed my mind,

To be constantly beseeching Thee.

I beseech a favour from Thee,

That I be purified from my sins,

Through the peaceful bright-shining flock.

The royal host whom I celebrate.”

http://omniumsanctorumhiberniae.blogspot.com.au/2013/03/saint-oengus-martyrologist-march-11.html

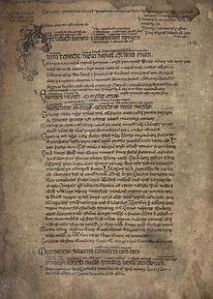

Excerpt from the Martyrology of Oengus, presenting the entries for 1 and 2 January in the form of quatrains of four six-syllabic lines for each day. In this 16th-century copy (MS G10 at the National Library of Ireland) we find pairs of two six-syllabic lines combined into bold lines, amended by glosses and notes that were added by later authors.

See also http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01173a.htm

http://li211-107.members.linode.com/index.php?title=Aengus_the_Culdee,_Saint

For the The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee (1905) on-line see, https://archive.org/details/martyrologyofoen29oenguoft and http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/G200001/