The Simple Life

An extract from an essay by the preeminent historian of simplicity, David Shi, the ‘foreword’ to “Simple Living in History: Pioneers of the Deep Future”, co-edited by Samuel Alexander and Amanda McLeod.

“The simple life is almost as hard to define as it is to live. It has also been with us for thousands of years. Simplicity is an ancient and universal ideal. Most of the world’s great religions and philosophies have advocated some form of simple living that elevates activities of the mind and spirit over material desires and activities. The great spiritual teachers of Asia – Zarathustra, Buddha, Lao-Tzu, and Confucius – all stressed that material self-control was essential to the good life. Greek and Roman philosophers also preached the virtues of the golden mean. Socrates was among the first to argue that ideas should take priority over things in the calculus of life.

People were ‘to be esteemed for their virtue, not their wealth’, he insisted. ‘Fine and rich clothes are suited for comedians. The wicked live to eat; the good eat to live.’

Aristotle refined this classical concept of leading a carefully balanced life of material moderation and intellectual exertion. ‘The man who indulges in every pleasure and abstains from none’, he observed, ‘becomes self-indulgent, while the man who shuns every pleasure, as boors do, becomes in a way insensible; temperance and courage, then, are destroyed by excess and defect, and preserved by the [golden] mean’.

A similar theme of simple living coupled with spiritual devotion runs through the Old Testament, from the living habits of tent dwellers in Abraham’s time to the strictures of the prophets against the evils of luxury. ‘Give me neither poverty nor wealth but only enough’, prayed the author of Proverbs. Jesus of Nazareth led and preached such a life of pious simplicity. He repeatedly warned of the ‘deceitfulness of riches’ and the corrupting effects of luxury, noting that gaining wealth too easily led to hardness of heart toward one’s fellows and deadness of heart toward God.

Simplicity has been an especially salient theme in Western literature. Chaucer repeatedly reminded readers of Jesus’s life of voluntary simplicity. Boccaccio took cheer in an open-air search for the spontaneous; Dante called upon his readers to ‘see the king of the simple life’; and Shakespeare offered the happiness of the greenwood tree. The Romantics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries likewise promoted a simplicity modelled after the serene workings of nature.

So much for simplicity as an historical ideal. In practice, the simple life has proven far more complex, varied, and challenging than such summary descriptions imply. The necessarily ambiguous quality of a philosophy of living that does not specify exactly how ‘simple’ one’s mode of living should be has produced many different practices, several of which have conflicted with one another. The same self-denying impulse that has motivated some to engage in temperate frugality has led others to adopt ascetic or primitive ways of living. During the classical period, for instance, there were many types of simplicity, including the affluent temperance of the Stoics – Cicero, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius, the more modest ‘golden mean’ of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, the ascetic primitivism of Diogenes, and the pastoral simplicity of Virgil and Horace. In asserting the superiority of spiritual over worldly concerns, some early Christians gave away all of their possessions and went to live in the desert as hermits. Others joined monasteries, and a few engaged in prolonged stints of abstinence and mortification. At the same time, many officials of the early church preached simplicity while themselves living in considerable comfort and even luxury.

Over the centuries, simplicity has also been embraced as a stylish fad. Benjamin Franklin’s self-conscious decision to wear an old fur cap and portray himself as a plain Quaker while serving as an American diplomat in Paris reflected his shrewd awareness that rustic simplicity had become quite fashionable among the French ruling class. Marie Antoinette’s famous playground, Hameau, constructed on the grounds of Versailles, was a monument of extravagant simplicity.

The toy village had its own thatched cottages, a dairy barn with perfumed Swiss cows, and a picturesque water mill. When the lavish life at court grew tiresome, the Queen could adjourn to Hameau, don peasant garb, and enjoy the therapeutic effects of milking cows and churning butter.

For such bored aristocrats, simplicity was clearly an affectation. But there have been many through the years who have practised simplicity rather than played at it. The names of St. Francis, William Blake, John Wesley, Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Mother Teresa come readily to mind. For them and others, simplicity entailed what William Wordsworth called ‘plain living and high thinking’. The degree of plainness differed considerably from individual to individual, as did the nature of the ‘high thinking’. They simplified their material activities in order to engage in a variety of enriching pursuits: philosophy, spiritual devotion, artistic creation, revolutionary politics, humanitarian service, or ecological activism.

In the Western experience, this ethic of plain living and high thinking has demonstrated similar diversity. As a way station between too little and too much, the ethic has encompassed a wide spectrum of motives and behaviour, a spectrum bounded on one end by religious asceticism and on the other by refined gentility. In between there is much room for individual expression. Some proponents of simplicity have been quite conservative in appealing to traditional religious values and or classical notions of republican virtue; others have been liberal or radical in their assault on corporate capitalism and its ethos of compulsive consumerism. In addition, class biases, individual personality traits, and historical circumstances have also combined to produce many differing versions of simple living in the Western experience…

American history is strewn with dozens of communal efforts at simple living, ranging from the Transcendentalist utopias at Fruitlands and Brook Farm in the 1840s to the hippie communes of the 1960s and 1970s.

Few of them, however, lasted more than a few months. Many of the participants in such alternative communities were naive about the hardships involved and lacked experience in the basic skills necessary for self-reliant living.

Yet the history of the simple life in the United States, as in the wider Western world, includes victories as well as defeats. That many of the ‘plain people’ have managed to retain much of their initial ethic testifies to their spiritual strength and social discipline. There have also been many successful and inspiring individual practitioners of simple living. As a guide for personal living and as a myth of national purpose, simplicity has thus displayed remarkable resiliency. It can be a living creed rather than a hollow sentiment or temporary expedient. During periods of war, depression, or social crisis, statesmen, ministers, and reformers have invoked the merits of simplicity to help revitalise public virtue, self-restraint, and mutual aid. In this way simplicity continues to exert a powerful influence on the nation’s conscience.

The ideal of simplicity, however ambiguous, however fitfully realised, survives because it speaks to desires and virtues harboured by all people. Who has not yearned for simplicity, for a reduction of the complexities and encumbrances of life? In the American experience, for example, the simple life remains particularly enticing because it reminds us of what so many of our founding mothers and fathers hoped the country would become – a nation of practical dreamers devoted to spiritual and civic purposes, a ‘city upon a hill’, a beacon to the rest of the world.

Today, simplicity remains what it has always been: an animating vision of moral purpose that nourishes ethically sensitive imaginations. It offers people a way to recover personal autonomy and transcendent purposes by stripping away faulty desires and extraneous activities and possessions. For simplicity to experience continued vitality, its advocates must learn from the mistakes of the past. Proponents of simplicity have often been naively sentimental about the quality of life in olden times, narrowly anti-urban in outlook, and disdainful of the beneficial effects of prosperity and technology. After all, most of the ‘high thinking’ of this century has been facilitated by prosperity. The expansion of universities and libraries, the democratisation of the fine arts, and the ever-widening impact of philanthropic organisations – all of these developments have been supported by the rising pool of national wealth. This is no mean achievement. ‘A creative economy’, Emerson once wrote, can be ‘the fuel of magnificence’…

As an ethic of self-conscious material moderation rather than radical renunciation, simplicity can be practised in cities and suburbs, townhouses and condominiums. It requires neither a log cabin nor a hairshirt but a deliberate ordering of priorities so as to distinguish daily between the necessary and superfluous, the useful and wasteful, the beautiful and vulgar. Wisdom, the philosopher William James once remarked, is knowing what to overlook. Mastering the fine art of simple living involves discovering the difference between personal trappings and personal traps. In this sense, simplicity is ultimately a state of mind, a well-ordered inner harmony among the material, sensual, and ideal, rather than a particular standard of living.

But is simplicity relevant to the complex corporate and consumer cultures that dominate modern life? Absolutely. Hidden beneath the surface appeal of life in the fast lane is the disturbing fact that the three most frequently prescribed drugs are an ulcer medication, a hypertension reliever, and a tranquiliser. In the United States, stress management has become one of the fastest growing industries. A hospital administrator recently observed that ‘our mode of life itself, the way we live, is emerging as today’s principal cause of illness’…

For people living in a press of anxieties, straining desperately, often miserably after more money, more things, and more status, only to wonder in troubled moments how to get off such a treadmill, the rich tradition of simplicity still offers an enticing path to a better life. Those hesitant to change the trajectory of their runaway lifestyles might ponder a question posed by the poet Adrienne Rich: ‘With whom do you believe your lot is cast? From where does your strength come?’

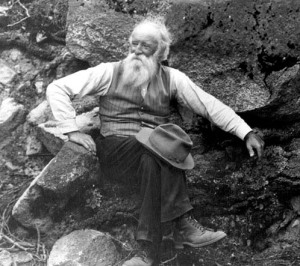

Those who choose an outwardly more simple and inwardly more fulfilling style of living discover that pressures are reduced, the frenetic pace of life is slowed, and daily epiphanies are better appreciated. Simpler living also benefits us all by reducing demands on our increasingly fragile and besieged environment. In addition, winnowing one’s money-making and money-spending activities can provide more opportunities for activities of intrinsic worth – family, faith, civic and social service, aesthetic creativity, and self-culture. The saintly naturalist John Burroughs acknowledged this fact in 1911 when the superintendent of the New York City schools asked him to share with students the secret of his good life.

‘With me,’ he remarked, the secret of my youth [at age seventy-four] is the simple life – simple food, sound sleep, the open air, daily work, kind thoughts, love of nature, and joy and contentment in the world in which I live. … I have had a happy life. … May you all do the same.

Samuel Alexander and Amanda McLeod (Eds)

“Simple Living in History. Pioneers of the Deep Future” [Simplicity Institute Publishing, 2014]

“The dominant culture of industrial civilisation is highly materialistic, holding up Western-style, consumer lifestyles as the path to happiness and fulfilment. But consumer lifestyles are failing to satisfy the human craving for meaning, and they are degrading our planet in ways that are grossly unsustainable and unjust. We desperately need to explore or rediscover less materialistic, ‘simpler’ ways of living.

‘Simple living’ refers to ways of life based on notions such as frugality, sufficiency, moderation, and mindfulness. This anthology brings together twenty-six short essays discussing the most significant individuals, cultures, and movements that have embraced simple living throughout history. What did Buddha and Jesus think about simple living? What contribution did the ancient Greeks and Romans make? How do the Amish and the Quakers live? And why did Henry Thoreau leave his hometown to live in the woods?

Readers will also gain insight into the lives and philosophies of people like Mahatma Gandhi and William Morris, and learn about contemporary eco-social movements, such as those based on permaculture, intentional communities, degrowth, and voluntary simplicity. This deep but engaging book examines these great moments in the story of simple living, and many more, but it looks backwards in order to shed light on the present and future.”

For The Simplicity Institute, see: http://simplicityinstitute.org/

For The Simplicity Collective, see: http://simplicitycollective.com/start-here/what-is-voluntary-simplicity-2

See also:

David E. Shi “The Simple Life: Plain Living and High Thinking in American Culture” [University of Georgia Press, 2007]

“Our current less-is-more impulse may have contemporary trappings, says David E. Shi, but the underlying ideal has been around for centuries. From Puritans and Quakers to Boy Scouts and hippies, our quest for the simple life is an enduring, complex tradition in American culture. Looking across more than three centuries of want and prosperity, war and peace, Shi introduces a rich cast of practitioners and proponents of the simple life, among them Thomas Jefferson, Henry David Thoreau, Jane Addams, Scott and Helen Nearing, and Jimmy Carter.

In the diversity of their aspirations and failings, Shi finds that nothing is simple about our mercurial devotion to the ideal of plain living and high thinking. “Difficult choices are the price of simplicity,” he writes in the book’s revised epilogue. We may hedge a bit in the practice of simple living, and now and then we are driven by motives no deeper than nostalgia. Shi stresses, however, that the diverse efforts to avoid anxious social striving and compulsive materialism have been essential to the nation’s spiritual health.”

“Our current less-is-more impulse may have contemporary trappings, says David E. Shi, but the underlying ideal has been around for centuries. From Puritans and Quakers to Boy Scouts and hippies, our quest for the simple life is an enduring, complex tradition in American culture. Looking across more than three centuries of want and prosperity, war and peace, Shi introduces a rich cast of practitioners and proponents of the simple life, among them Thomas Jefferson, Henry David Thoreau, Jane Addams, Scott and Helen Nearing, and Jimmy Carter.

In the diversity of their aspirations and failings, Shi finds that nothing is simple about our mercurial devotion to the ideal of plain living and high thinking. “Difficult choices are the price of simplicity,” he writes in the book’s revised epilogue. We may hedge a bit in the practice of simple living, and now and then we are driven by motives no deeper than nostalgia. Shi stresses, however, that the diverse efforts to avoid anxious social striving and compulsive materialism have been essential to the nation’s spiritual health.”

http://www.ugapress.org/index.php/books/simple_life/1/0

For David Shi, see: http://davideshi.com/

Leave a comment